I recently decided to see Death of a Unicorn — a new film written and directed by Alex Scharfman, and released by A24 on March 28, 2025 — based on little more than the need for some end-of-workweek entertainment, my trust that A24 films will be reasonably well done and weird and vibey (essentially my baseline ask for any artwork), and its official tagline:

“A father and daughter accidentally hit and kill a unicorn while en route to a weekend retreat, where his billionaire boss seeks to exploit the creature’s miraculous curative properties.”

Mythical creatures and exploitative capitalists? Sure, why not!

But about a third of the way through, my engagement with the movie suddenly deepened considerably.

The main teenage protagonist Ridley (played by Jenna Ortega) is feeling uncomfortable about both the way her father Elliot (played by Paul Rudd) has brought her to his wealthy boss’s house to play on his sympathies — they both recently suffered the loss of Ridley’s mother, and billionaire Odell Leopold thinks Elliot showed fortitude throughout the tragedy — and the unicorn they hit on the drive in and stashed in the trunk of their car, who may or may not be entirely dead.

There’s a moment when Ridley, alone in her guest room at the Leopold mansion, flips through photos of her dead mother on her phone for emotional support. She pauses on one with an image of a unicorn in the background and zooms in. “Unicorn Tapestries, Cloisters!” I thought to myself, fractions of a second before Ridley types this exact search phrase into her phone, which I’ll have to admit was quite a satisfying moment of recognition and confirmation for me.

From then on, it became clear to me that the film’s project — as writer and director Alex Scharfman has confirmed in multiple interviews — was to reset the narrative of these medieval tapestries in our contemporary world.

Pulling centuries-old stories that still resonate into the present day? A 2025 artwork based on c. 1495-1505 artworks hanging in a museum I’ve visited many times?1 Now, this movie was extremely my vibe and, of course, potentially rich terrain to explore here on Lit in One Sentence.

So, how does one transmute medieval tapestries into contemporary film? Can superstructure be our guide even when the original narrative appears only in a static visual format?

Usually, this is where I would put my emotional superstructure sentence into the post, describing the film’s main character, their journey, and what’s at stake so we can talk about it more. But this time, I think it would be more fun to look at story depicted on the tapestries before seeing how the retelling was structured.

This is a free post, but will contain some spoilers for the film. As always, if you read the spoilers then watch the movie, you’ll simply get to enjoy the story with the perceptual fluency of a second-time viewing.

How to Retell Medieval Tapestries in Contemporary Cinema

In attempting to understand this “retelling” of a series of visual artworks, my first question is: do these tapestries have their own emotional superstructure? That is, do they have a clear focal character whose emotions we could potentially inhabit, undergoing an articulable journey, with evident stakes?

I’ve never attempted to answer this question for a single image like, say, a painting. I would probably have to try (maybe in a future post?) to know whether or not it works in any meaningful way.

But this is a set of seven tapestries, with something of an arc, so maybe it could function like a comic or graphic narrative, telling a clear story over the course of that arc.

Some background: From the weaving techniques and clothing of the men and women depicted, it’s likely that these tapestries were designed in France and woven in Brussels right around the year 1500. They appear for the first time in written records in the late 1600s, at which time they were hanging in the bedroom of a French nobleman. They continued in his family’s possession until the Revolution, after which they spent time keeping the potatoes of some peasants warm, until a descendant of the family tracked them down and reclaimed them. They remained in this family until John D. Rockefeller purchased them, gifting them to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in the 1930s. They are hanging in the Museum’s medieval branch, the Cloisters, to this day. The only other surviving set of medieval unicorn tapestries in the world is at the Musée de Cluny in Paris.

If you are interested in doing your own deep dive into the history and symbolism, you can learn more on the Met’s website (with high resolution images and descriptions), through these two Cloisters guidebooks from the 1970s that are available as free PDF downloads, and through this quick overview with images at The Public Domain Review.

For our purposes, let’s take a quick look at the panels and evaluate whether any obvious narrative structure for a contemporary A24 film reveals itself.

The first panel is “The Hunters Enter the Woods.” No obvious unicorn yet, but a member of the hunting party, standing in a grove in the upper right corner, signals that he might have seen something.

In the second panel, “The Unicorn Purifies Water,” the unicorn dips its horn into water flowing from a fountain, to purify a stream poisoned by a snake (the Devil), while a menagerie of exotic beasts and the hunting party (it would have been unsportsmanlike to give chase before their prey began to run) watch on in awe. Healing power is a major theme, here and throughout unicorn lore.

In “The Unicorn Crosses a Stream,” the hunting party surround their quarry and aim their weapons.

In “The Unicorn Defends Himself,” he gores a hound and kicks a hunter.

The fifth panel, “The Unicorn Surrenders to a Maiden,” survives only in fragments, but we see the unicorn, somewhat surprisingly, tamed at the feet of a maiden, even calmly allowing a dog to lick its wounds. The fragment with a hunter blowing his horn suggests that this peace will not last, however.

The maiden who has tamed the unicorn is depicted mostly in the lost part of the tapestry, only her sleeve visible at the animal’s throat. But it is to her that the unicorn looks up adoringly. The woman we can see more completely is probably one of her ladies in waiting, signalling something to the hunters.

In “The Hunters Return to the Castle,” the unicorn is finally killed in the top left of the panel, and brought back draped across a horse (with many symbolic allusions to the Passion of Christ) at the panel’s center. The denizens of the castle watch on, their reactions seemingly somewhat ambivalent at the success of this hunt.

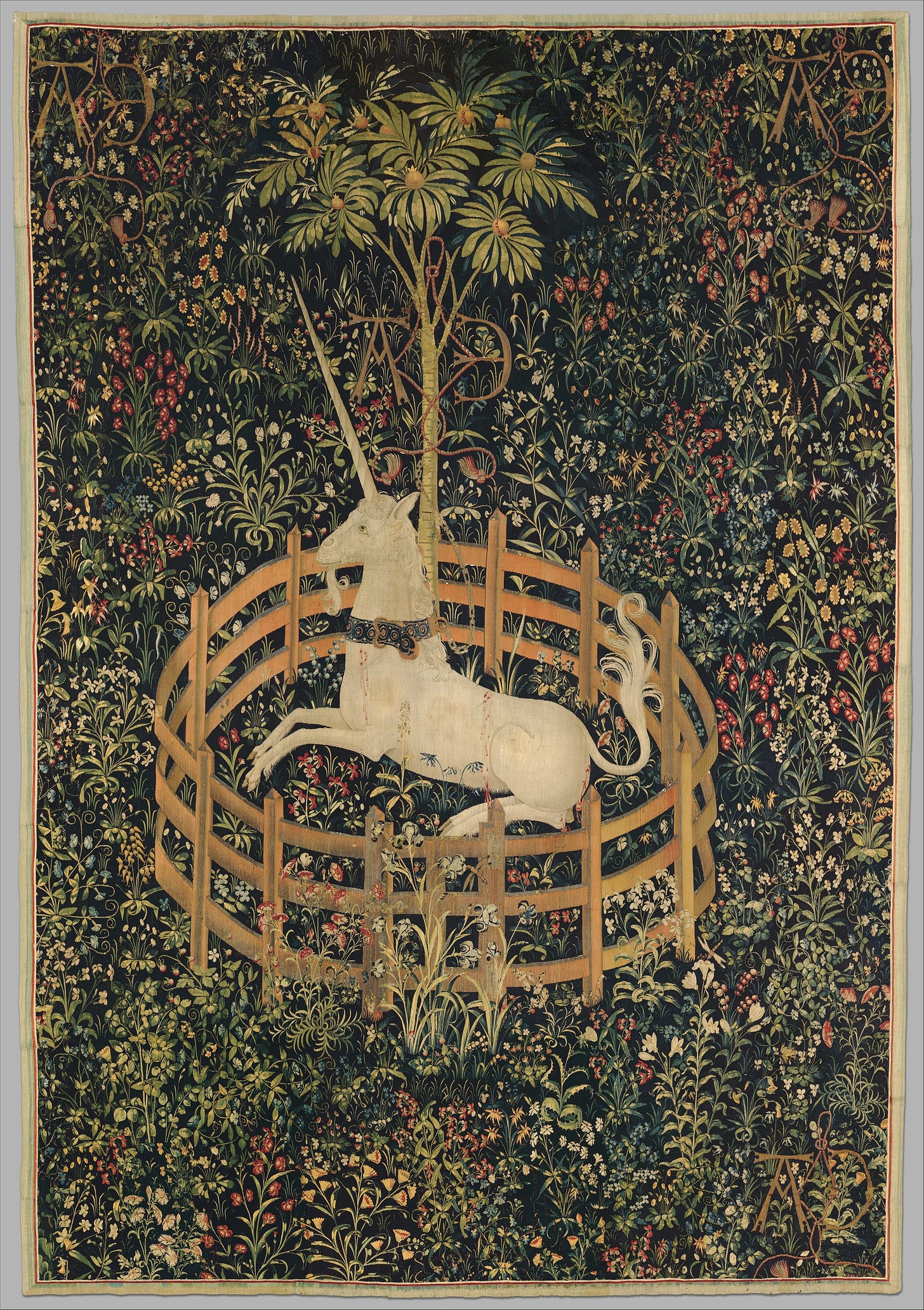

In the final panel, “The Unicorn Rests in the Garden,” the unicorn has been resurrected and is enclosed within a fence in a field of flowers. Its chains do not bind it tightly, meaning it has more or less acquiesced to its captivity. The red liquid dripping down its flank is not blood but pomegranate juice, a medieval symbol of fertility and marriage. So in this one, the unicorn might symbolize a bridegroom acquiescing to his capture by a fair maiden.

Apparently, medieval audiences would have had no problem interpreting the series of tapestries as intermingled allegories of both Christ and marriage, the unicorn representing both Jesus and an ordinary human bridegroom.

That’s great for them, but so far does not give us much of a narrative structure on which to base a contemporary A24 film.

And, luckily, the filmmakers do not try to push either the unicorn-as-Christ or the marriage plot at all. With a very quick nod to the historical Christian symbolism in one line of dialogue, they proceed to have teenage Ridley—a vaping, septum-pierced interpretation of the “virtuous maiden” in panel five—give her own read on what the tapestries mean, which grounds us in how unicorns and their human hunters function within this particular film’s storytelling.

Which is really all we need to know to enjoy the story. As with any story, it just needs to make sense internally on its own terms, regardless of how the tapestries’ symbolism might function outside the story world.

Researching the tapestries, Ridley tries to puzzle out the elements of their narrative that might be relevant to her situation: that even a unicorn that has been killed won’t necessarily stay dead, that they will fight back against their human hunters, and that they can only be tamed by a virtuous maiden. This is how the tapestries’ symbolism functions inside the story world.

So the focal character in the A24 film, the one whose emotions we will primarily mirror throughout, is the “virtuous” maiden, Ridley. What makes her so virtuous, compared to everyone else around her?

The Lit in One Sentence approach to zeroing in on this is to ask: what’s at stake for Ridley, that’s different from what’s at stake for everyone else around her?

Well, she cares about her dad. She’s already lost her mom. She does not care at all about her dad’s billionaire boss and has had a bad feeling about this weekend retreat at his family’s weird mountain mansion all along. After they hit the unicorn, all she really wants is to grab her dad and get out of there. So, she cares about her family.

But actually, so do all the other characters, to some extent. Which is worth unpacking a little, because it’s not always a given in these types of movie scenarios.

Even the sinister billionaire pharmaceutical family all kind of seem to care about each other. The patriarch is dying of cancer and, at first, I was half-expecting his wife and/or son to be disappointed when he is miraculously cured by the unicorn’s blood, anticipating the sort of plotline where they were waiting eagerly for him to die so they could inherit all the money and power and do whatever they want with it.

But no, the wife does seem reasonably fond of her husband. The son does want to win his parents’ approval. They just all quickly pivot to thinking about how they can maximally exploit this miraculous cure, making a lot of money (as if they need any more) while appearing to do a lot of good in the world. While, perhaps, actually doing a lot of good in the world, because isn’t curing human beings of horrible diseases ultimately a good thing?

Unfortunately, as the scientists in the company’s employ soon point out, unicorn blood will be impossible to replicate. Whatever they want to use and promise to “their people” (as the mom puts it) will have to come from actual unicorns.

Which brings us to the non-billionaire adults in the film: the scientists and Ridley’s father, an attorney. What’s at stake for them? Money, since they actually have to worry about it to some extent. Ridley’s dad promised her dying mom he would make sure their daughter was always provided for, which he interprets in an extremely material sense. He’s also just a very career-focused guy, meaning career advancement is also a big motivator for him.

At one point, he’s conspiring with one of the scientists to make sure they’re not left out of the benefits of discovering the unicorn panacea, or dependent on the billionaire family both surviving and choosing to do right by them once the dangers have passed. They remind each other of why they’re doing all this, only the scientist says “our families” while Ridley’s dad says “our careers,” before quickly correcting himself that the careers are of course ultimately about providing for the families.

All of this is happening against a backdrop of rampaging unicorns from the forest who seem determined to break into the mansion grounds and kill all the people within. And even the scientist who is stealing a vial of powdered unicorn horn only to provide for her family soon gets savagely gored to death.

So, caring about and trying to protect her family isn’t what makes Ridley uniquely “virtuous” enough to tame the unicorns.

What is it then?

The answer isn’t fully revealed until the end, which makes it the most spoilery. But if you don’t mind, read on.

As Ridley surmised from the tapestries, a unicorn that has been killed doesn’t necessarily stay dead. They can heal themselves as much as they can heal anyone else, in this story’s world. And they have families too.

The unicorn that Ridley and her dad struck at the beginning of the film — whose remains have never quite stopped “kicking,” despite all the dismemberment in the name of science and curing humans — is a baby. And the rampaging pair that emerges from the forest to gore all the un-virtuous adults are, as Ridley eventually figures out, its parents. They want all the parts of their baby back so they can bring it back to life.

And Ridley is the only human who wants that for them, more than she wants anything for herself. Even when her dad gets fatally wounded near the end of the film, her instinct is not to run for unicorn parts to try to heal him, but to simply hold him and share her profound experience of touching the unicorn horn (at the beginning of the movie) with him, at his request.

She is the only one unwilling to destroy the unicorn family in order to save her own.

And this, naturally, makes all the difference. The unicorn parents witness it and decide to help her out, throwing her dad’s body on the heap of their own kid’s parts as they bring it all back to life.

In the medieval version of the tapestries, the maiden’s “virtue” likely referred to her virginity and perhaps her Christian piousness, whatever that meant at the time.

In the contemporary retelling, the key seems to be not breaking up or exploiting other families (even animal families) in order to benefit one’s own.

I’m a little surprised to find myself so won over by the latest creature feature’s definition of “virtue,” but I feel that in this case the answer is really satisfying! And pretty on point for our times.

If you agree, you can support the filmmakers by checking it out in theatres. And I would love to hear what you think in the comments (which live below the paywall).

The Emotional Superstructure of Death of a Unicorn

Though every adult around her is determined to exploit its miraculous healing properties, a teenager must return a dead baby unicorn’s remains to its rampaging parents for resurrection.

Fun fact: When I lived within an hour’s drive of The Met, the guards at the garage saw me so often they stopped searching my car and started guessing what exhibit or event I was there for instead.